8

the existence of potential self-control problems through

the lifecycle, may be able to implement commitment

devices to counteract personal biases and prevent a

premature spending of personal savings, while a naïve

individual would not (Laibson, 1997, Angeletos et al,

2001). Examples of such commitment mechanisms in

financial products are the classic use of illiquid housing

equity as a vehicle for saving, and the partial illiquidity of

retirement savings accounts which imposes tax penalties

to early withdrawals. Lastly, it has been empirically

documented that self-awareness of potential biases

has a positive effect on retirement savings even after

controlling for measures of IQ, financial literacy and

socio-demographic characteristics (Goda et al, 2015).

The relationship between present bias and retirement

savings, driven by the documented existence of

heterogeneous sophisticated and naïve agents, makes

financial regulators and service providers interested

in understanding the benefits of such commitment

technologies in financial products. It became critical

to understand how salient they should be in order

to correctly inform policy and effectively generate

behavioural changes. This question was experimentally

addressed recently by Beshears et al (2015) using a

representative sample of the U.S. adult population. The

authors pointed out that: (i) conventional economic

theory predicts that nothing should be contributed to a

commitment account when it offers the same expected

return as a fully-liquid account. (ii) higher penalties

may reduce premature withdrawals, but they may also

discourage deposits, defeating the goal of raising net

savings; on the other hand, (iii) if savers recognize that

penalties help them overcome self-control problems,

they may welcome higher penalties and make more

deposits in response. In sum, they test whether the

demand for commitment savings accounts is affected by

how illiquid the offered savings accounts are.

Commitment devices have been shown as strongly

appealing. When participants were asked to allocate

money between a liquid account and a commitment

account that randomly varies across participants in

terms of interest rates, prohibitions and penalties for

withdraws prior to a commitment date, they presented

a consistent demand for commitment technologies.

Participants allocated around half of their endowments

to the commitment account when there was no

difference in interest rates between the two vehicles,

and one-quarter of their money even when the interest

rate paid by the commitment account was lower than the

liquid account. These results build on previous evidence

from field experiments on the role of commitment

savings accounts performed in different countries (see

Beshears et al, 2015, p.3). Ultimately, this suggests the

presence of sophisticated present-biased individuals in

the U.S. adult population.

An anxious reader might think that policymakers

should set high withdraw tax penalties on pension

plans because this act would benefit all agents and the

aggregate national level of savings. Although, we need

to consider that sophisticated players are only part

of the market, if not the minority, hence generating

an ambiguous effect of higher withdraw penalties

on total contributions to these accounts that is not

irrespective of how heterogeneous the population in

question is. First of all, financial products like private

and workplace pension plans, given their risk profile and

asset allocations, have expected returns that are higher

than vehicles with immediate liquidity, such as current

account deposits. Beshears et al (2015) show that when

the commitment account presented in their framework

paid an interest rate higher than the liquid account,

as is the real case of pension schemes, the empirical

relationship between illiquidity levels and deposits in

the commitment account was insignificant, suggesting

that the U.S. adult population contains also naïve

present biased individuals and/or individual who have

consistent time-preferences, i.e., without present bias.

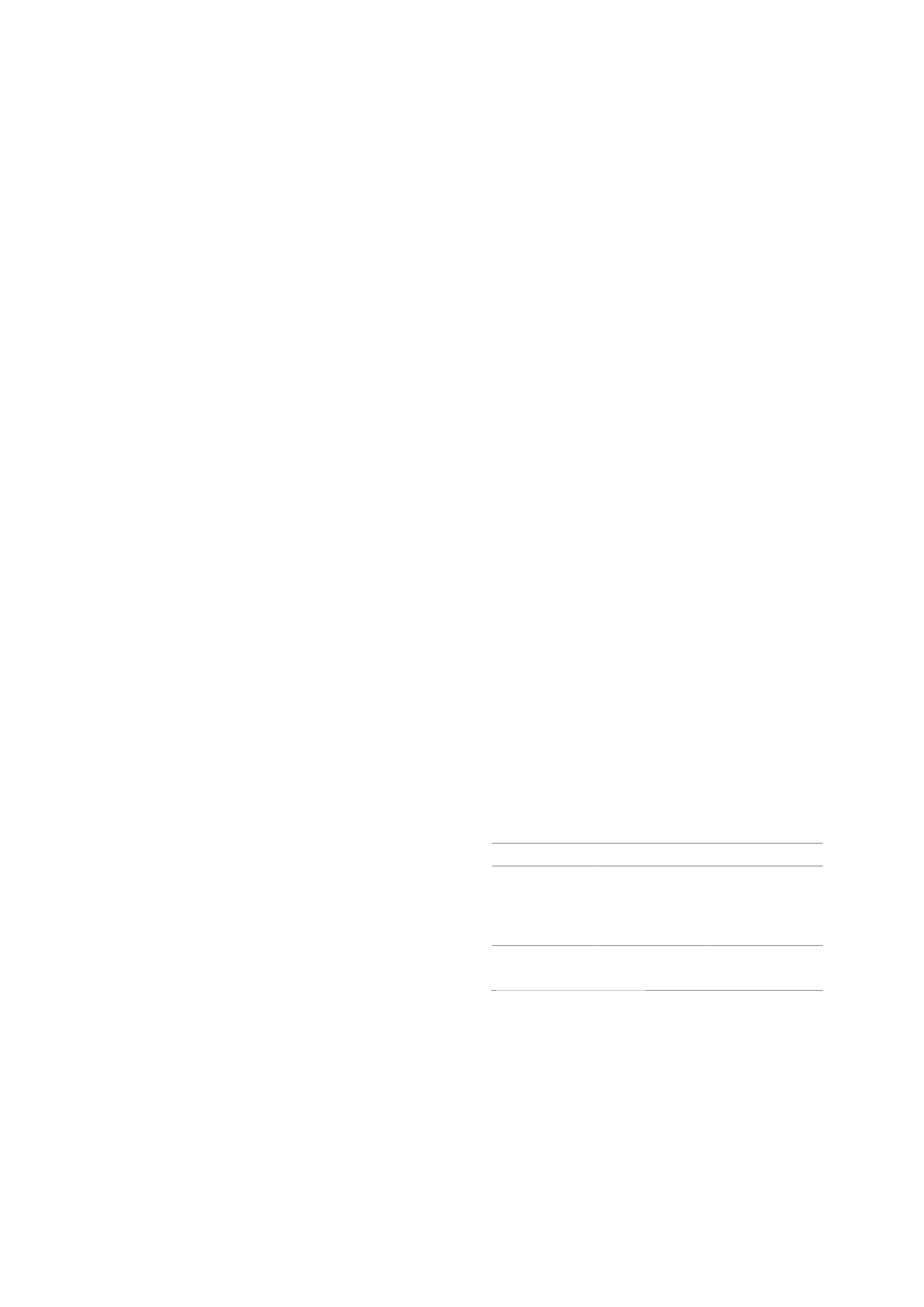

The interaction of these two other groups is described in

Table 1. Both make positive commitment deposits that

diminish as the commitment account’s illiquidity rises.

This ends up offsetting the increase in commitment

deposits by the group of sophisticated present-biased

individuals.

Table 1. Relationship between illiquidity levels and de-

posits in commitment accounts

For further references of the lessons learned and to

be learned about the interaction between present

bias, self-control and commitment devices, we suggest

the recent review of O’Donoghue and Rabin (2015).

The study proposes a set of research questions, being

among them: how to assess the impact of present bias

against other phenomena?; and how to assess whether

the demand for commitments are due to present bias?

4

private and workplace pension plans, given their risk profile and asset allocations, have

expected returns that are high r than vehicles with immediate l qui ity, such as current

account deposits. Beshears et al (2015) show that when the commitment account

presented in their framework paid an interest rate higher than the liquid account, as is

the real case of pension schemes, the empirical relationship between illiquidity levels

and deposits in the commitment account was insignificant, suggesting that the U.S.

adult population contains also naïve present biased individuals and/or individual who

have consistent time-preferences, i.e., without present bias. The interaction of these two

other groups is described in Table 1. Both make positive commitment deposits that

diminish as the commitment account’s illiquidity

rises. This ends up offsetting the

increase in commitment deposits by the group of sophisticated present-biased

individuals.

Table 1. Relationship between illiquidity levels and deposits in commitment

accounts

Group characteristic

Without present bias

With present bias

Sophisticated

Deposits decrease as

illiquidity rises because

this group has time-

consistent preferences.

No need for commitment

devices.

Deposits increase as

illiquidity rises because

this group is aware of

their bias and potential

self-control problems.

Naïve

Deposits decrease as illiquidity rises because naïve

agents are unaware of whether biases and potential

self-control problems.

Note: based on Beshears et al (2015).

For further references of the lessons learned and to be learned about the interaction

between present bias, self-control and commitm nt devices, we sugg st the recent

review of O’Donoghue and Rabin (2015). The study proposes a set of research

questions, being among them:

how to assess the impact of present bias against other

phenomena?

; and

how to assess whether the demand for commitments are due to

present bias

? In sum, the recent studies of Delaney and Lades (2015). Goda et al (2015)

and B sh ars et al (2015) provide good initial evaluations to address these questions to

better inform policymaking in the context of retirement savings.

2. Conclusions

Increasing the illiquidity pension schemes may not increase aggregate contributions

because only one segment of the population has the desire for strict commitment in

order to stick with a previous decided plan. This highlights the need for further

developments to deal with innocent unsophistication of the naïve group. Enhancing

financial literacy and the access to professional advice can be potential complementary

mechanisms.