Press, Journal Article

4

as-yet-unstated level. The uncertainty of selling all those bonds may

spook the bond market. Consider that a few words from former Fed

chairman Ben Bernanke spoken in spring of 2013 sparked a 150 basis

point sell off in 10-year Treasuries (the so-called “Taper Tantrum”),

which, in turn, spiked mortgage rates and sent home sales into a re-

newed slump.

The minutes of the March 2017 FOMC meeting show that the Fed

prefers a “passive and predictable” roll-off of both Treasuries and

MBS.

5

We learned in June 2017 what this would mean. The unwind

process will permit $6 billion of Treasury securities and $4 billion

of agency debt and mortgage- backed securities (MBS) to roll off

the Fed’s balance sheet each month. Note: the Fed will not be selling

assets, only collecting the coupon, principal and maturity payments

below the $10 billion monthly “cap” and returning those proceeds to

the U.S. Treasury—just like any normal bond investor might sweep

maturities out of a portfolio to meet payroll obligations instead of

selling a bond. If future economic conditions warrant shrinking the

balance sheet further, every three months the initial caps will increase

by $6 billion (Treasuries) and $4 billion (agency and MBS), up to a

maximum of $30 billion in Treasuries and $20 billion in agency and

MBS per month.

In the meantime, since the future is unknown, we’ve mapped out three

scenarios for the balance sheet (

see Figure 3 on page 3

). Even in the

“aggressive” scenario in which the Fed ceased all reinvestment of the

proceeds of its bond portfolio today—and maintained that policy for

four years—the balance sheet would still exceed $2 trillion in 2021.

Further, as mentioned above, the balance sheet would have grown

naturally without the crisis of 2008. A simple extrapolation at the his-

torical rate of growth in demand for the nation’s currency of 7% puts a

floor under the balance sheet over time (the gray line).

Given what we know now, our best guess is that by decade’s end the

balance sheet will still be $2-3 trillion. But the intersect between those

two lines may end up being higher. In short, a big balance sheet in

dollar terms is here to stay—we are not going back to $800 billion.

6

EMBRACE THE BIG BALANCE SHEET

Inquiring bond investor minds want to know: what does the unwind

mean for interest rates? Telling the tale above is absolutely necessary

for understanding what might happen next. We reach several conclu-

sions, first concerning short-term rates and second longer-term rates.

The Fed’s control of short-term rates has been successful so far, and

the Fed’s ability to control the federal funds rate and other short-term

interest rates will remain the key tool of monetary policy. All else

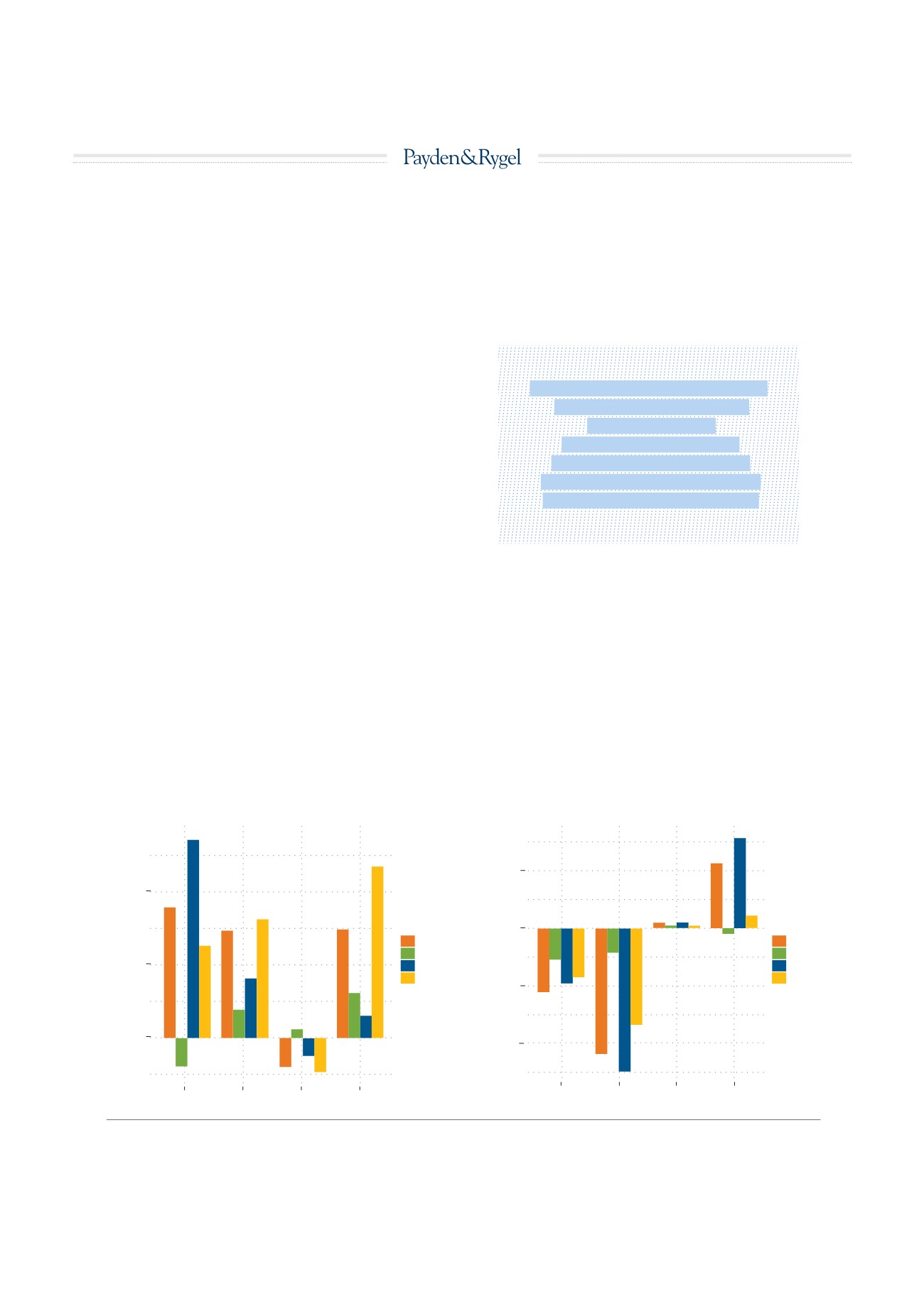

Change in Yields

DURING

QE Programs

Source: Federal Reserve, Payden Economics

Change in Yields 12 Months

AFTER

QE Programs

2-year

30-year

5-year

10-year

Tenor

Yield Change (%)

0.8

0.4

0.0

2-year

30-year

5-year

10-year

Tenor

Yield Change (%)

0.5

0.0

-0.5

QE1

QE2

Twist

QE3

Program

-1.0

QE1

QE2

Twist

QE3

Program

WHAT DOES THE BALANCE SHEET MEAN FOR THE LONG-END OF THE YIELD CURVE? IT IS HARD TO SAY.

fig. 4

«THE LESSON: INVESTORS

SHOULD INFER VERY

LITTLE ABOUT

THE DIRECTION OF

LONGER-TERM RATES

FROM CHANGES IN THE

FED’S BALANCE SHEET.»

50