Press, Journal Article

1

O

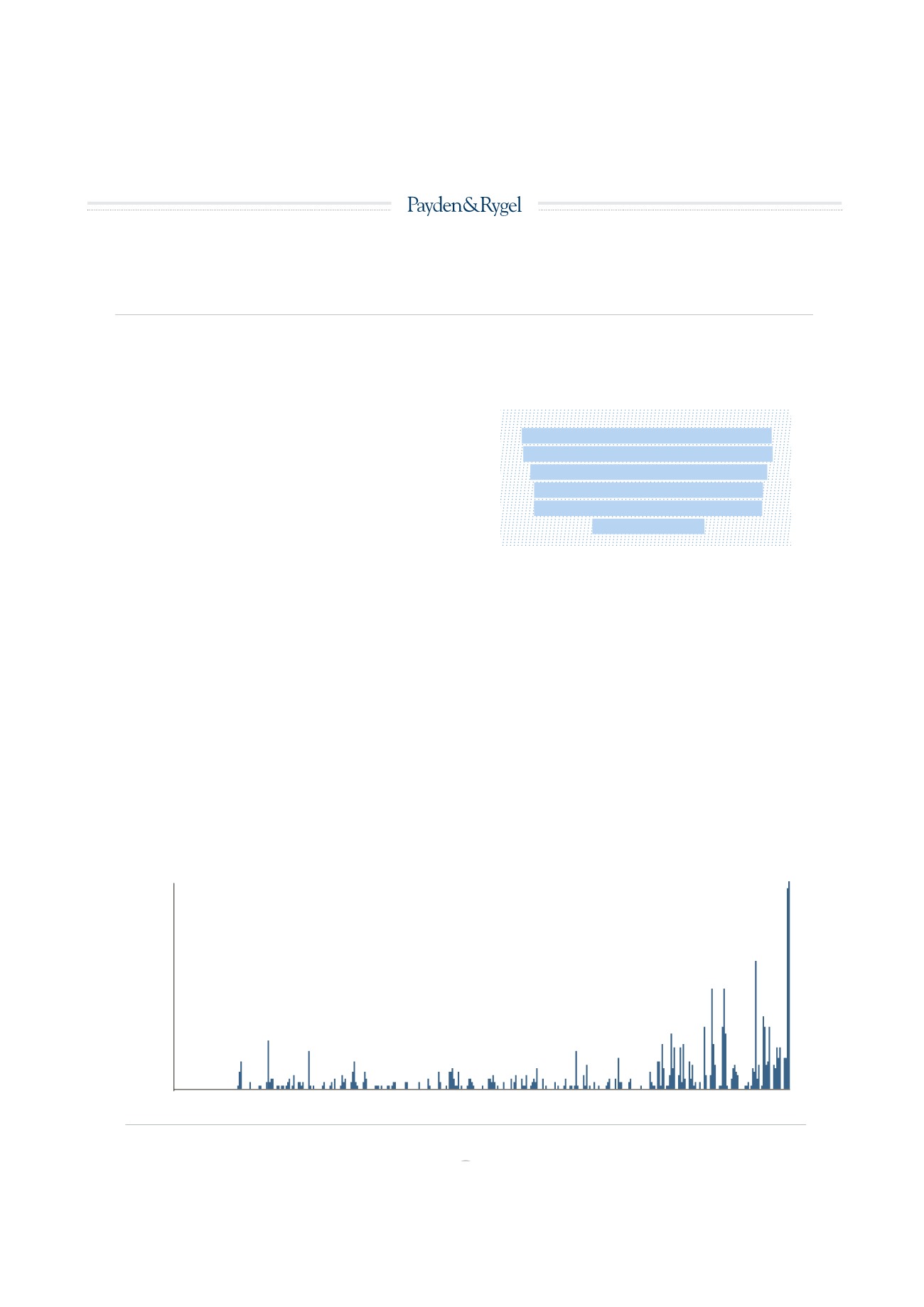

ne of the most discussed topics in 2017 has been the Federal

Reserve’s bloated balance sheet and the steps the Fed might take

to reduce the bloat. Interest in the topic has reached a fevered pitch of

late, with the number of media stories referencing the “Fed’s balance

sheet” spiking (

see Figure 1

).

The Fed itself has fanned the flames of market worries by suggesting

that an unwind could begin soon and by publishing research to show

that successive quantitative easing (QE) programs boosted equity

prices by 11-15%, depressed longer-term interest rates by around 90

basis points (or 0.90%) and weakened the U.S. dollar versus its peers

by up to 5%.

Given these alleged market impacts as the balance sheet grew, it is

natural for investors to wonder whether the unwind will cause waves

as the tide rolls out. Or, as one bond market observer remarked,“Who

will buy all those bonds if the Fed isn’t buying?”

1

We say, worry not.

We think the Fed will seek to avoid a“Taper Tantrum 2.0” at all costs.

Dire economic and market consequences from the Fed’s balance sheet

will be more imagined than real. And the big balance sheet is here

to stay, as the Fed has discovered a new role for itself in the money

markets.

THE BALANCE SHEET BASICS: THE GOOD OLD

DAYS

Understanding a central bank’s balance sheet requires a few basics.

The primary purpose of the Fed’s balance sheet—or that of any cen-

tral bank for that matter—is to back the nation’s currency. To that

end, the Fed holds assets to match its liabilities, which comprise the

nation’s money, in the form of bank reserves and physical currency.

Circa 2007 (before the balance sheet ballooned), most of the Fed’s

balance sheet consisted of Treasury bills on the asset side and cur-

rency on the liability side (

see Figure 2 on page 2

). In those days, as

bank lending and deposit creation progressed, demand for currency

and reserves increased. The balance sheet grew at roughly 5-7% per

year for several decades, coincident with nominal spending growth

(remember this, it will be important later).

Bank reserves were a tiny share of the Fed’s liabilities.Then, as now, all

depository institutions held bank reserves at the Fed, as prescribed by

law, to meet minimum“reserve requirements.”Think of bank reserves’

function like an individual’s checking account, save one detail: unlike

a personal checking account, banks can temporarily skirt overdrafts.

H ow W e L earned to S top W orrying

and L ove the F ed’s B ig B alance S heet

«THE PRIMARY PURPOSE OF

THE FED’S BALANCE SHEET—

OR THAT OF ANY CENTRAL

BANK FOR THAT MATTER—

IS TO BACK THE NATION’S

CURRENCY.»

Number of Stories

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Jul

2016

Source: Bloomberg

Feb

2016

Mar

2016

Apr

2016

May

2016

Jun

2016

Aug

2016

Sep

2016

Oct

2016

Nov

2016

Dec

2016

Feb

2017

Jan

2017

Mar

2017

MEDIA HOOPLA AROUND THE “FED’S BALANCE SHEET” TAKES OFF IN 2017

fig. 1

47